Reviewed by Cecilia Busby

Available on Kindle

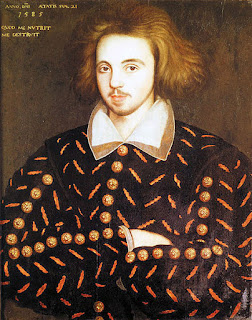

"Christopher Uptake" is a curious book. I have an original copy of it, illustrated with a picture of a rather serious young Elizabethan man, bending over some writing in a dark room, illuminated only by a candle. The newly issued Kindle cover has an immediately recognisable portrait of an altogether more confident character, gazing at the viewer with a hint of challenge in his eyes.

The motto on the original portrait (below) is "Quod me nutrit me destruit" - that which nourishes me also destroys me. In Elizabethan times the motto was associated with a torch or candle held upside down - the falling wax causing the candle to burn more brilliantly but also eventually extinguishing the flame. The image reminds me of Edna St. Vincent Millay's "My candle burns at both ends, it will not last the night; But ah my friends and oh my foes - it gives a lovely light!" The lovely light, was, of course, the short but brilliant career of Christopher Marlowe, poet, dramatist, atheist and spy, whose wild living and controversial opinions may have led to his murder at the age of 29.

Christopher Uptake is clearly based on Marlowe - yet strangely that link is not made in the blurb for either the original or the re-issued book, despite the portrait on the front. Nor do any of the Amazon reviews mention it. It seems odd. Uptake, like Marlowe, is the son of a tradesman, a grammar-school boy who wins a scholarship to Cambridge, an atheist who takes to writing plays, and who gets mixed up in the Elizabethan secret service, spying on the equivalent of Second World War fifth columnists: the English Catholics. Yet Uptake is not Marlowe; his trajectory is, finally, very different. Rather than taking to the business of spying with gusto, Uptake is riven with doubts. He suffers from stabs of conscience and from guilt at the thought of what his spying may lead to for the Catholics taken and tortured by the Elizabethan secret police. Uptake is a reluctant spy, caught in a net where his cooperation is ensured by threats to himself and his family. He is represented as a miserable collaborator with a harshly repressive state regime.

It's a long way from the swashbuckling image of Marlowe the dramatist, with the "high astounding terms" of his bravura verse, his reputed love of "tobacco and boys", and the boast that "he had as good a right to coin as the Queen of England and ... meant through help of a cunning stamp-maker to coin French crowns, pistolets and English shillings". I have to confess to having fallen half in love with this version of Marlowe when I was sixteen and first discovered Tamberlaine the Great. In the preface to my secondhand copy of his Collected Works was a reproduction of the infamous Baines Note, detailing Marlowe's supposed blasphemies. That, for example, "all Protestants are hypocritical asses", and "if he were put to write a new religion he would undertake both a more excellent and admirable method" as "all the New Testament if filthily written". Like the later Marx, he argued that "the beginnings of religion was only to keep men in awe", and that "Moses was a juggler". Doubts have been cast on how much of this was really Marlowe's opinions and how much was malicious slander - but I was hooked: by the poetry, the drama, and the blasphemies.

Reading "Christopher Uptake", I wondered whether Susan Price had set out to write about Marlowe and then found that she couldn't make it work. Simply couldn't find a way "in" to a character who was so obviously intelligent and free-thinking and yet came to work as a spy for the government, betrayed those he had feigned friendship with, professed a Catholic faith only to entrap and incriminate others. Perhaps she just couldn't prevent the guilt and the doubt overwhelming her Christopher, unlike the historical one, to the point where he had to become Uptake rather than Marlowe. It seems curious, otherwise, to stick so closely to the original and yet give her character's story such a different resolution. Certainly the book made me think much more deeply than I have before about what it would have been like to live in the time of Elizabeth I, what it really meant to be surrounded by such a strong network of spies and agents provocateurs, to live in the middle of rumour, plots, counterplots, agents and double-agents. It would have been, I think, a little like living in Berlin at the height of the Cold War. Uptake is a young man who wants to be left alone, doesn't want to do anyone any harm; yet in such times it's hard to stay neutral, and Christopher struggles in the sticky webs laid by the Queen's spymasters.

I

was really gripped by Christopher's predicament, by his moral dilemmas

and justifications, as well as his attempts to limit the damage he has

done. Price does an excellent job of making his world believable, making

us care about Christopher, making us desperate for him to escape the

clutches of the sinister spy, Bagthorpe. It's a book that lives on in

the imagination after it's read, and it certainly made me think again

about the real Christopher Marlowe and what he may or may not have done

in the service of the unscrupulous Sir Francis Walsingham (pictured).

I

was really gripped by Christopher's predicament, by his moral dilemmas

and justifications, as well as his attempts to limit the damage he has

done. Price does an excellent job of making his world believable, making

us care about Christopher, making us desperate for him to escape the

clutches of the sinister spy, Bagthorpe. It's a book that lives on in

the imagination after it's read, and it certainly made me think again

about the real Christopher Marlowe and what he may or may not have done

in the service of the unscrupulous Sir Francis Walsingham (pictured).I think there are ways to understand Marlowe's role as a spy, particularly when you remember that England at the time was a small and insecure island, surrounded by great Catholic powers simply waiting for a chance to invade. It was a crueller time, life was more fragile and more contingent. But Susan Price's Christopher is a fine creation that certainly serves as a challenge to anyone who admires the playwright: what made Marlowe choose differently from Uptake?

Cecilia Busby writes as C.J. Busby

She is the author of Frogspell, Cauldron Spells, Ice Spell and Swordspell

www.frogspell.co.uk

Return to REVIEWS HOMEPAGE

1 comment:

Thank you, Cecilia! My Christopher was inspired by Marlowe, just as my Sterkarms were inspired the Armstrongs - but in both cases I came to the conclusion that, although I didn't mind it being obvious where the inspiration came from, I didn't want to be bound by history either. Both Christopher and Sterkarms are fiction, and I wanted to be able to follow my own fictional path in whatever direction it happened to go.

As for Marlowe - when I was reading about him, I found that there were as many Marlowes as there were researchers. Gay Marlowes, straight Marlowes, violent Marlowes - even devout Catholic Marlowes, as well as Marlowes who survived Deptford and busily wrote Shakespeare's plays for him...

Post a Comment